Integrating conservation in multi-disciplinary consultancies

Conservation specialists often work in smaller practices but major infrastructure projects tend to demand more complex project management skills and input from a wider range of professional disciplines. Jennifer Murgatroyd makes the case for using multidisciplinary consultancies on this kind of project.

|

| Cross-trained geophysicists and structural engineers work together to survey a historic façade using roped access, ensuring accurate collection of geophysical data within the proper construction context. |

Without its cultural narrative, what makes any partially-ruined farmhouse, for example, worth saving? From a conservation standpoint, the inherent value of heritage assets lies in the contexts of architectural style, history of use, location, age and so on. The heritage statements which must be attached to any application for listed building consent can be the silver bullet in the armoury of the heritage professional looking to ‘save’ a building from destruction or redevelopment into oblivion. We must remember, though, that the concept of historic conservation, at its core, comprises a great deal more than simply rehabilitating ageing buildings.

The ultimate goal of a redevelopment plan is, or should be, not just saving a historic structure or site from destruction, but actually allowing it to thrive, to maintain its usefulness within the community while preserving its inherent cultural value. A complete history of the building in a heritage statement that documents reconstructions or refurbishments can actually inform and improve the project beyond simply controlling the extent of potentially negative heritage impact.

One example was at the University of Hertfordshire, where refurbishment works were complicated by the presence of 18th-century chalk mines. As part of the planning process, consultants were engaged to conduct geophysical surveys to precisely locate subsurface voids associated with the historic mine works. The surveys provided the client with a more complete understanding of their building site and ultimately produced important documentation of the extent and location of historic industrial works. Armed with this map of a potentially dangerous system of subsurface voids, the project engineers were able to mitigate potential dangers prior to the start of construction works. In this case, scientists working together with heritage professionals to better understand the heritage asset improved, rather than hindered, the client’s plans for refurbishment.

Of course, successful conservation projects must ultimately present a satisfactory business case. This means that project design must satisfy commercial interests – including budget constraints, health and safety, project scheduling or project management – alongside planning mandates. Sometimes this calls for creative solutions. One development in London found itself in just this position.

The objective was to preserve the cultural narrative of an important streetscape by retaining the historic façade of an unlisted building within a conservation area, while the structure behind it underwent a substantial redevelopment. Although façade retention schemes like this damage significance, they do allow internal structures to be modernised. RSK was employed to investigate the pre-works condition of the façade and to locate and inspect the steel framework behind the cladding. The sensitive nature of the building and materials meant that standard access and testing procedures were not possible, so a combined team from various departments worked together to deliver bespoke, non-destructive analysis of the façade. Specially-trained geophysical and civil engineers used roped access to conduct the investigation of the stonework in situ, enabling each of the teams to draw on the others’ expertise. The geophysicists were able to accurately collect and interpret technical data using specialist kit, while the engineers guided the investigation using specialist knowledge of early construction techniques and materials. All team members were trained by the Industrial Rope Access Trade Association, so they were able to complete the survey while suspended from the roof of the building.

Issues of place and cultural history are just one aspect taken into consideration during all phases of planning for development. While heritage consultants are busy outlining the cultural-historic limits to development, consultants from other fields provide guidance in other areas of environmental concern. Issues of ecology or health and safety, to take two simple examples, can limit plans for development, restrict timings or stretch budgets. Just as a building’s historic features will limit the extent of reconstruction allowed, the presence of bats or even the right conditions for bats can affect when a roof can be replaced. The discovery of asbestos can stop work across an entire site until avoidance and mitigation strategies are in place. The mine exploration project above is an example of heritage meeting health and safety.

Badger setts, protected trees, nesting birds and great crested newts are just a few more examples of natural assets that must be considered and mitigated during development. Because many protections must be guaranteed, a number of early phase surveys must be undertaken. Even for a single structure these works can be expensive, complicated and time-consuming. The requirements can become exponentially more complex for large-scale infrastructure projects such as railway improvements, power line upgrades or motorway-widening schemes.

The Planning Act of 2008 commissioned a review body for planning applications relating to infrastructure projects that are in the national interest and required detailed environmental assessments. These are required for projects related to energy, transport, water resources and waste treatment, or general infrastructure projects that are in the national interest. Such works may span long distances, crossing multiple conservation areas or AONBs, and they may take some years to complete. Applications for a development consent order must be found to satisfy the requirements of minimal effect, avoidance or mitigation of negative impact to the ecology and environment, as well as to heritage assets, across all aspects of the planned project and for the duration of the works, or beyond if appropriate. Practical considerations, such as nesting sites or habitats for protected species are considered alongside any questions of historic preservation within a given area.

A review of the decisions as published by the secretary of state for the Department of Energy and Climate Change illustrates that these applications have in fact been refused in cases where a project has the potential to negatively impact the historic character of an area or to harm protected species, waterways or public access to a site. The importance of pre-application surveys cannot be overstated because the life of a project depends on the quality of investigation, thoroughness of reporting, and perhaps even creativity when it comes to mitigation strategies. The work of specialist consultants is paramount to the ultimate project design. A large number of reports from a large number of specialists (scientists, engineers, surveyors, and archaeologists for example) must be collated to develop a coherent, workable and cost-effective development plan that addresses all of the appropriate concerns.

Many projects have been completed successfully by marshalling the efforts of individual sub-contractors from each of the relevant disciplines required for a full investigation report that covers the length and breadth of the project area. The difficulty in this approach is greater than simply finding and engaging the right specialists – no simple feat in itself – but in coordinating their respective efforts and relating their works one to another. Spare a thought for the project managers who must plan a development that avoids or minimises damage to heritage assets, while also scheduling the work to avoid the activities of nesting birds in the area, but only once the asbestos insulation has been removed from all 40 or so structures along the route.

As the cost of these investigations must naturally be written into the project budget, employing a consultancy that provides numerous services can be a cost-effective approach. Time, effort and costs for mobilisation can be saved by coordinating the efforts of specialist consultants, an approach made easier when specialists all come from the same consultancy. Archaeologists, say, can attend geotechnical trial pitting to watch for sub-surface archaeology, but working as a single team with the geotechnical personnel they can work from the same risk assessment and on the same insurance, possibly sharing vehicles and kit. The overall impact of the mobilisation in terms of carbon footprint, number of vehicles on site and ultimate cost can be streamlined by the multidisciplinary consultancy.

The Brechfa Forest Connection Project, for example, saw a wide variety of specialists from the same consultancy called upon to work together to deliver a complex package of works. Western Power Distribution planned to connect the Brechfa Forest West wind farm in Carmarthenshire to the electricity distribution network, a project that required nearly 30km of power lines, including areas of both overhead lines and buried cables. This line would pass through challenging topography in a designated special landscape and crossed a river that has been designated a site of special scientific interest and a special area of conservation. The scope of work provided by the consultancy included specialists from a number of disciplines: land use, agriculture, and forestry; landscape and visual impact; protected species surveys and habitats regulations assessment; heritage impact assessments; geology, hydrogeology and ground conditions; drainage and flood risk assessments; noise and vibration; air quality; socioeconomic studies; and GIS mapping of the area. If this list seems a bit unwieldy, it illustrates the scope of investigation required in such studies before the application for development is even filed. Because of the in-house, cooperative approach, it was possible to offer comprehensive input at all stages of the client’s planning process.

|

| Brechfa Forest West, Carmarthenshire: connecting a wind farm to the electricity distribution network required nearly 30km of overhead lines and buried cables crossing challenging topography and sensitive landscape |

The multidisciplinary nature of the project team made it possible to provide the client not only with a package of factual, descriptive survey data of environmental factors at risk, but also with evidence-based advice on feasible options for the route corridor location and alignment throughout multiple phases of the project. The team was also able to engage with local landowners, the local council and National Resources Wales to discuss the findings at various stages throughout the survey and environmental scoping process. This holistic approach allowed for a more complete service to the client.

The application for development consent was ultimately accepted with a decision that cited the project’s good design and its consideration of a long list of potential impacts, including the historic environment.

While the ‘one-stop-shop’ approach is perhaps simpler to organise and less costly for the client, there are additional benefits to an integrated consultancy. Specialists can produce better results if they work together to inform each other’s projects in a holistic way. Working from the same office, they can learn from each other, strengthening their own experience, extending their own expertise, providing better value to their clients. After enough outings with an ecologist, an architectural historian may come to recognise the signs of bat roosts. In which case he or she can flag up the need for a full survey, thereby saving the client from potentially costly and damaging violations.

When scientists, specialists and project planners combine forces they can ensure all facets of the business case are met. This, after all, is the only way to ensure projects are fully funded, which in turn is the best way to ensure that heritage assets are fully protected. A well-designed project will produce a series of records that document the history of a particular structure: the ‘state of things’ when work began, what was done and why. All of this could be presented as a benefit, integrating any conservation works or development into the history of a structure or conservation area, actually celebrating modern changes as part of an ongoing story rather than an unfortunate inevitability.

This article originally appeared in IHBC's 2017 Yearbook. It was written by Jennifer Murgatroyd DPhil Oxon, a senior geomaterials scientist with the Materials & Structures Department at RSK Environment. She is a historic materials specialist with a particular focus on lime mortars. She is also an honorary visiting researcher at the Department of Archaeological Sciences at the University of Bradford and an affiliate member of the IHBC.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

- AONBs.

- Archaeologists.

- Conservation areas.

- Development consent order.

- Ecology.

- Geophysical surveys.

- Habitats regulations assessment.

- Heritage assets.

- Historic environment.

- IHBC articles.

- Protected species.

- Roped access for conservation projects.

- Site of special scientific interest.

- Special area of conservation.

- The Institute of Historic Building Conservation.

IHBC NewsBlog

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

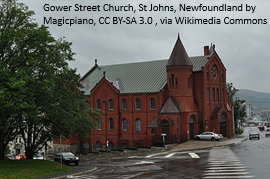

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?

131 derelict buildings recorded in Dublin city

It has increased 80% in the past four years.